Gibbs’ reflective cycle was developed by Dr. Graham Gibbs in 1988 – a research leader in the Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences at the University of Huddersfield. Gibbs’ reflective cycle is a framework giving structure to the process of learning from experience through six stages: description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusions, and action plan.

| Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Concept Overview | Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle, developed by Graham Gibbs, is a structured framework for reflection, often used in education and professional development. It provides a systematic approach to analyzing experiences, focusing on learning from past situations, and improving future actions. |

| Six Stages of Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle | This model consists of six distinct stages, each guiding a specific aspect of the reflective process: Description, Feelings, Evaluation, Analysis, Conclusion, and Action Plan (or Action). Reflectors move through these stages sequentially to explore their experiences fully. |

| Description | The first stage involves describing the event or experience in detail. Reflectors outline the context, setting, people involved, and any other pertinent information. This stage lays the foundation for a comprehensive reflection by creating a clear picture of the situation. |

| Feelings | In this stage, individuals express their emotions and thoughts regarding the experience. Reflectors explore their initial reactions and feelings, acknowledging any positive or negative emotions they might have experienced during the event. |

| Evaluation | The evaluation stage entails making a value judgment about the experience. Reflectors consider what went well and what could have been done differently. This stage encourages self-assessment and an objective review of one’s performance or actions. |

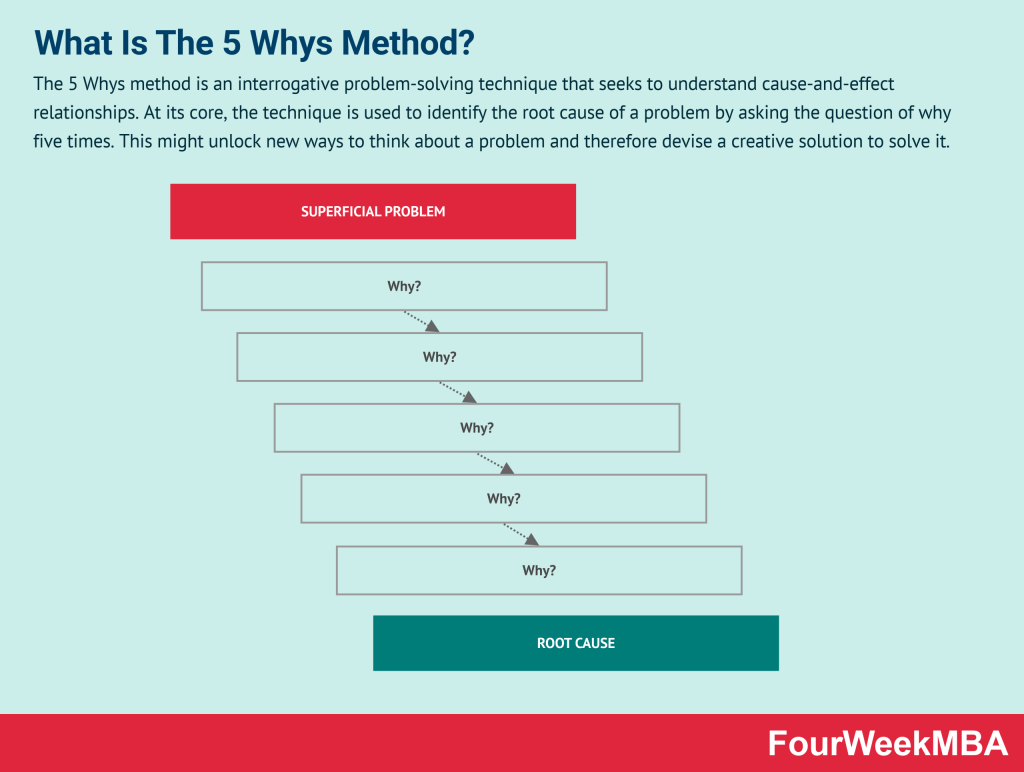

| Analysis | During this stage, individuals delve deeper into the experience, attempting to understand the underlying factors, reasons, and dynamics. Reflectors analyze the situation from various perspectives, exploring the “whys” behind their actions and feelings. |

| Conclusion | The conclusion stage involves summarizing the key insights gained from the reflective process. Reflectors reflect on the overall lessons learned and takeaways from the experience. This stage helps in consolidating the learning and identifying areas for improvement. |

| Action Plan (Action) | The final stage of the cycle is all about planning for future actions or changes based on the reflection. Reflectors set concrete goals, strategies, or action plans to apply what they’ve learned to similar situations or avoid making the same mistakes in the future. |

| Implications | – Structured Reflection: Provides a systematic framework for reflective practice. – Comprehensive Exploration: Encourages thorough examination of experiences from multiple angles. – Learning and Improvement: Focuses on using insights to enhance future actions and decision-making. |

| Benefits | – Enhanced Self-Awareness: Helps individuals better understand their thoughts, emotions, and actions. – Continuous Learning: Facilitates ongoing learning and development through reflection. – Improved Decision-Making: Encourages informed choices based on past experiences and insights. |

| Drawbacks | – Rigidity: Some individuals may find the structured nature of the model constraining. – Time-Consuming: Requires a significant amount of time and effort to go through all six stages. – Limited Applicability: May not be suitable for every type of reflection or learning context. |

| Use Cases | – Education: Widely used in educational settings, including teaching, training, and student assessment. – Professional Development: Helps professionals in fields like healthcare, social work, and counseling enhance their practice. – Personal Growth: Useful for personal self-reflection and improvement. |

Understanding Gibbs’ reflective cycle

In his work entitled Learning by Doing, A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods, Gibbs noted that it was

“not sufficient simply to have an experience in order to learn. Without reflecting upon this experience it may quickly be forgotten, or its learning potential lost. It is from the feelings and thoughts emerging from this reflection that generalisations or concepts can be generated and it is generalisations that allow new situations to be tackled effectively.”

Fundamentally, Gibbs’ reflective cycle supports experiential learning through a structured debriefing process.

Experiential learning is simply the process of learning by experience, but it’s worth noting that the technique also considers that one’s education and work also impact the way they learn and understand new knowledge.

The nature of the framework as a cycle means it can be used for continuous improvement of repeated experiences, enabling the practitioner to learn and plan based on things that went well and others that did not.

With that in mind, the cycle can also be used to reflect on singular, standalone experiences unlikely to be repeated.

Whether by accident or by design, Gibbs’ reflective cycle has been an influential force in teacher development programs and also across a variety of different health professions.

In truth, however, the cycle is useful for any practitioner who finds themselves studying, practicing, or teaching the skills of critical reflection.

Gibbs’ reflective cycle advantages and disadvantages

Advantages

Learning can happen both in structured and unstructured ways.

At the business level, having a framework like Gibbs’ reflective cycle can be extremely helpful as a review process for individuals within the organizations.

It’s therefore critical, for the framework to work, to follow its steps, from description to action plan.

Gibb’s reflective cycle structures the process of learning from experience through six stages: description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusions, and action plan, thus enabling anyone within an organization to assess what happened and how to improve.

In that respect, this framework helps individuals within organizations to develop a better understanding of their capabilities as they move to a structured way to assess any situation by first analyzing it objectively.

And only after looking at it from an emotional standpoint.

The analysis and action plan make it possible to improve and become way more balanced in assessing business situations moving forward.

In that respect, Gibbs’ reflective cycle is a simple to implement model, with clear and structured steps that can help improve professionally.

Disadvantages

For Gibbs’ reflective model to work, it needs to be done objectively, and there needs to be a sincere analysis of the situation at hand by the person using it.

A superficial assessment of the situation and a lack of judgment about what happened can make the framework useless.

Indeed, especially in the analysis part, it’s critical to frame the event as objectively as possible, making it possible later to assess it from an emotive standpoint.

Only by following the process with an open-minded approach (where you’re ready to get involved in the process) can the model really enable you from a professional standpoint.

The six stages of Gibbs’ reflective cycle

| Stage | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Description | Describe the situation or experience in detail. Include the who, what, when, where, and why. | During a nursing shift, I had to deal with a difficult patient who was uncooperative and verbally abusive. |

| 2. Feelings | Examine and express your emotions and thoughts during the experience. | I felt frustrated, overwhelmed, and irritated by the patient’s behavior. I was also concerned about providing quality care. |

| 3. Evaluation | Analyze the situation by considering what went well and what didn’t. | What went well: I maintained my composure and continued to provide care. What didn’t go well: I struggled to establish rapport with the patient. |

| 4. Analysis | Reflect on the experience by exploring its significance and identifying lessons learned. | I realized that I need to improve my communication and conflict resolution skills to handle challenging patients better. |

| 5. Conclusion | Summarize the key insights and what you learned from the experience. | I learned that effective communication and remaining patient-centered are essential when dealing with difficult patients. |

| 6. Action Plan | Develop a plan for future actions or changes based on what you’ve learned. | In future interactions with challenging patients, I will use active listening, empathy, and de-escalation techniques. |

Each of the six stages of Gibbs’ model encourages the individual to reflect on their experiences through questions.

Following is a look at each stage and some of the questions that may result.

1 – Description

In the first stage, the individual has an opportunity to describe the situation in detail.

It’s important to remain objective – feelings, thoughts, emotions, and inferences can be described later.

Individuals should provide a detailed account of what happened, who was involved, and what actions were taken.

The purpose of this initial stage is to provide a clear and objective picture of the experience so that the individual can reflect on and recall the event in more detail.

Some helpful questions include:

- What happened?

- Who was present?

- When and where did it happen?

- What were the actions of the people involved?

- What was the outcome?

2 – Feelings

Now is the time to explore feelings or thoughts associated with the event.

To do this, it is important for the individual to look back on their emotional state and any rational thoughts about the situation itself.

The purpose of this stage is primarily to help someone understand the impact of the event on their emotions and how it affected them.

The feelings stage also allows them to derive insights from their emotional responses and identify any underlying problems that require attention.

Some questions to ask in the second stage include:

- What were you feeling before, during, and after the event?

- What do you believe other people were thinking or feeling?

- What do you think about the situation now that some time has passed?

3 – Evaluation

Evaluation means determining the positive and negative aspects of the event – regardless of whether you consider the event to be one or the other. Again, objectivity is key.

Objectivity enables the individual to make value judgments, which are evaluative statements of how good or bad they believe an idea, action, or situation to be.

Value judgments are often prescriptive in the sense that they reveal how the individual perceives the world via certain attitudes and behaviors.In the third stage, objectivity can also be increased when the individual considers the experiences and perspectives of other people.

Some pointers include:

- What was good and bad about the experience?

- What did you contribute to the situation?

- Did your actions have a positive or negative impact? Repeat the question to consider the contributions of others.

4 – Analysis

During the analysis stage, you have a chance to understand what happened using theory and context.

This step should comprise the bulk of your reflection and should take into account any insights gleaned from the previous steps.

In the process of analyzing the situation, the individual should always try to make sense of it and distinguish fact from fiction.

It can also be helpful to consider whether their experiences differ from others.

To do this, co-workers and those who can provide quality input can be consulted for assistance.

However, diverse opinion should be balanced with research of the literature and relevant theories to better understand what transpired.

Some helpful questions include:

- Why did things go well or go badly?

- How does your experience compare to academic literature, if applicable?

- Could you have responded differently?

- Are there theories or models that can help you understand what happened?

- Are there factors likely to have contributed to a better outcome?

5 – Conclusions

In the fifth stage, conclude what happened by summarising key findings and reflecting on changes that could improve future outcomes.

When making conclusions, the individual must consider how they will impact them on a personal level.

After which, they can think about what the conclusions mean for their immediate context and then more broadly when others are involved (such as in a team, workplace, or department).

This step should be a natural and intuitive response to the previous steps. It may incorporate questions such as:

- What did the situation teach you? You can be rather general or more specific.

- How might the situation have been more positive for all concerned?

- What skills or competencies are required to handle the situation more effectively?

6 – Action plan

Lastly, an action plan is crafted to detail how you will respond differently to a similar situation in the future. The plan is important in making sure good intentions are backed by action.

The action plan stage is one of the most important for obvious reasons.

It involves the identification of specific steps that need to be taken to improve a similar future experience or prevent an event from occurring in the future.

Ultimately, action plans help individuals develop strategies for future improvement and growth.

They can take a proactive (not reactive) approach to their experiences and use them as a tool for personal development.

To get you in the right of mind, consider these questions:

- What would you do differently when faced with a similar situation? How would your new skills or knowledge be applied?

- How can you make sure you act differently when faced with a similar situation in the future?

- How and when will you develop the required skills?

Gibbs’ reflective cycle example – getting a promotion

Imagine that you have recently been promoted to a regional management position for a supermarket chain.

As part of your new role, you are required to oversee multiple store managers ensure sales in your region meet stated targets.

1 – Description

Now, imagine it is your first day on the job and you drive out to visit your first store.

You have difficulty imposing yourself on the manager of the store, despite the fact he is a subordinate.

The matter is exacerbated by the presence of a senior manager, your direct superior, who is spending the day with you to ensure a seamless transition and is watching your every move.

Customers also look on as the discussion, which concerns a promotional display at the front of the store, becomes heated.

The disagreement causes the store manager to walk away while you are expressing your point of view.

This is the description stage of Gibbs’ reflective cycle. Now, let’s take a look at the others.

2 – Feelings

As with most people who start in a new position, you were likely nervous, anxious, or uncertain about what would happen on your first day.

You may also have been insecure about your authority and fearful that it may be challenged by a subordinate who was used to the previous, more lenient regional manager.

During the event, you felt a mixture of shame and embarrassment as the altercation was playing out in front of customers.

You were also worried that your direct supervisor would start to second-guess his decision to promote you.

After the event, most of these emotions have dulled somewhat and you start to realize that the actions of the store manager do not necessarily reflect your ability to lead others.

3 – Evaluations

The good part of this experience was that you at least attempted to assert your authority about the promotional display.

While it was received poorly by the store manager, he must understand that this will be the nature of our relationship moving forward.

Furthermore, it must be remembered that many employees resistant to change react with negative emotions.

The bad part of this experience was the fact that the whole experience had to play out in public.

Our customers are our number one priority and it would have been preferable for the discussion to be held in private.

My failed attempt to move to the discussion elsewhere may have contributed to the situation.

4 – Analysis

On analysis, the situation occurred because a store manager who was accustomed to the status quo reacted badly to a change in management approach.

The presence of the senior manager in the store may have also worsened the fear and distrust that often accompanies change.

Multiple change management frameworks confirm this to be a common occurrence.

Nevertheless, maybe you could have responded differently by disarming the store manager in some way.

You could have smiled more or let him take you on a tour of the store and left the heavy-handed managerial directives for another day.

5 – Conclusions

The situation taught you that building relationships with subordinates is as important as it is with friends, family, superiors, and colleagues.

Some subordinates – particularly those with some degree of seniority themselves – will be reluctant to obey your commands point-blank.

The situation could have been handled better by easing into the transition.

Perhaps you could have visited the store beforehand and held an informal lunch with the store manager so that the both of you could get to know each other.

6 – Action plan

Given that you have 16 stores under your supervision, you realize the importance of developing an action plan to avoid a potential repeat of the situation.

As part of this plan, you undertake extra company training on management techniques and learn power phrases that can be used to disarm verbal aggression.

You also learn how to better read someone’s body language and build rapport with your store managers.

This is seen as a more beneficial alternative than talking about business objectives right away and potentially alienating them forever.

If a situation does arise in the future, you know that these techniques and training will help you neutralize demonstrative behavior and avoid tensions escalating.

Drawbacks of Using Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle:

While Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle is a valuable tool for self-reflection and learning, it has some limitations and potential drawbacks:

1. Subjective Nature:

The reflective process is inherently subjective, relying on an individual’s perceptions and interpretations, which may not always align with objective reality.

2. Time-Consuming:

The process of going through all the stages in the cycle can be time-consuming, which may deter individuals from engaging in reflective practice regularly.

3. Complexity:

Some individuals may find the structured nature of the cycle complex, especially if they are new to reflective practice.

4. Limited in Specific Fields:

Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle may be more applicable to certain fields (e.g., education, healthcare) than others, potentially limiting its universal use.

5. May Not Address Complex Ethical Dilemmas:

For complex ethical dilemmas, the cycle may not provide sufficient depth or guidance in decision-making.

When to Use Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle:

Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle is valuable in various scenarios:

1. Educational Settings:

It is commonly used in educational settings to encourage students to reflect on their learning experiences, identify areas for improvement, and enhance critical thinking skills.

2. Professional Development:

Professionals in fields like healthcare, social work, and teaching use the cycle to review their practice, make improvements, and ensure continuous development.

3. Decision-Making:

It can be applied when making important decisions, particularly those involving ethical considerations, to explore the consequences and underlying values.

4. Personal Growth:

Individuals seeking personal growth and self-improvement can use the cycle to reflect on life experiences and set personal development goals.

How to Use Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle:

Implementing Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle effectively involves following a structured process:

1. Description:

Describe the experience or situation you want to reflect on, providing context and details of what happened.

2. Feelings:

Examine your emotional response to the experience. What were your feelings and thoughts at the time?

3. Evaluation:

Evaluate the experience, considering both positive and negative aspects. What went well, and what could have been done differently?

4. Analysis:

Analyze the experience by exploring its significance, what you learned from it, and any underlying issues or challenges.

5. Conclusion:

Draw conclusions from your analysis. What can you generalize from this experience? What insights have you gained?

6. Action Plan:

Identify specific actions you can take to apply what you’ve learned to future situations. How can you improve your practice or make informed decisions?

What to Expect from Implementing Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle:

Implementing Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle can lead to several outcomes and benefits:

1. Improved Self-Awareness:

Through reflection, individuals gain a deeper understanding of their thoughts, emotions, and reactions in various situations.

2. Enhanced Decision-Making:

Reflective practice can lead to better-informed decision-making by considering past experiences and their consequences.

3. Continuous Learning:

It promotes a culture of continuous learning and improvement, both personally and professionally.

4. Problem-Solving Skills:

It enhances problem-solving skills by encouraging individuals to analyze and evaluate their experiences.

5. Professional Growth:

Professionals can use reflective practice to enhance their skills, adapt to new challenges, and meet the evolving needs of their roles.

6. Ethical Considerations:

It provides a structured approach to exploring ethical dilemmas and making decisions in alignment with one’s values and principles.

In conclusion, Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle is a valuable framework for self-reflection and learning.

While it has its drawbacks and complexities, understanding when to use it and how to apply it effectively can lead to improved self-awareness, decision-making, and personal and professional growth.

By following the steps outlined in the cycle and recognizing its potential benefits and drawbacks, individuals and educators can leverage Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle to enhance their reflective practice and learning experiences.

Gibbs’ reflective cycle example – startup accelerator

1 – Description

Suppose that an entrepreneur is part of a start-up accelerator and, at the culmination of their three months with the company, has the opportunity to pitch their business idea to a room full of attentive investors.

The entrepreneur wants to start a D2C cake business and is in the process of refining their business model and pitch in time for the presentation.

2 – Feelings

When the individual first joined the accelerator, they were excited, enthusiastic, and optimistic about the future.

As the entrepreneur started to delve into the details of running a business, however, they realized that much more work was required to understand market trends, identify the main competitors, and provide cost estimates.

Cost estimates were the most significant concern.

The entrepreneur had hoped to cost a brick-and-mortar store in a desirable location for the business plan, but the preliminary cost for a store in several different areas was deemed prohibitive.

Cost estimates

Feeling somewhat dejected, the entrepreneur reverted to a pop-up stall that could be moved at will.

However, when she rang the city council about a mobile food vendor permit, they advised her that the cost was based on the number of square meters the stall occupied.

Having not purchased one yet, she became more frustrated.

Eventually, the entrepreneur joined a social media group for food vendors in her city and obtained cost estimates for several different sizes from others.

She then fed this data into the business plan and researched the average attendance at various city events to estimate her potential target audience.

While the development of a business plan has been stressful and at times bewildering, the entrepreneur starts to feel more confident in her ability to run a successful cake business without the future support of the accelerator.

Ultimately, she pitches to the room full of attentive investors and one decides to invest in her company based on her concise and accurate business plan and demonstrated initiative.

3 – Evaluation

In the evaluation phase, the now business owner felt that her idea of questioning others in the same industry was rather effective.

Most were happy to provide constructive feedback – despite the fact that some would become future competitors.

The fact that she was able to attract the attention of an investor is an obvious plus.

So what was bad about the experience?

For one, despite being surrounded by qualified support, she could have asked for help earlier to avoid stress later on.

She was also frustrated at the city council’s perceived disinterest in providing a quote.

4 – Analysis

In the analysis phase, the entrepreneur concludes that some things went wrong initially because of her lack of organization and her inability to ask for help.

In the case of the latter, she didn’t know what she didn’t know about small business and this hindered her progress.

This ignorance, if you will, has been described and studied extensively in the literature.

Developed by management trainer Martin Broadwell, the four stages of competence is a framework that describes the process of an incompetent person transitioning to competence in a certain skill or topic.

5 – Conclusion

To conclude, the entrepreneur ascertains that the situation taught her to be patient, resilient, and to leave her ego at the door when considering whether to ask for help.

The problem with the city council quote, which involved a somewhat rude and terse conversation, could have been improved if she was aware of how the council quoted beforehand.

Having said that, the entrepreneur does acknowledge that her stress level was high before the call was made.

6 – Action plan

To better deal with a similar situation in the future, the cake entrepreneur will use her awareness of the link between poor preparation and stress.

In other words, if she is better prepared, she will not be as stressed when dealing with others.

Reasoning that there is much more she doesn’t know about small business, she also decides to enroll in a part-time course and join her city’s local business association.

Lastly, the entrepreneur researches ways to be more comfortable with asking for assistance. As part of her action plan, she writes the following four pointers:

- Help others before asking for help.

- Know what you want to ask before asking.

- Ensure the question is SMART: specific, meaningful, action-oriented, real, and time-sensitive.

- Never assume to know what or who people know.

Gibbs’ reflective cycle – HR staff member

In this example, an HR staff member uses Gibbs’ reflective cycle to reflect on the process of rewarding or recognizing employees from different seniority levels.

1 – Description

The process starts with the employee researching employee rewards and the factors that motivate them to perform. The individual is responsible for developing incentive programs for both junior employees and senior executives.

Based on their research, they determine that each cohort needs to be rewarded in a different way to increase motivation.

For junior employees, rewards should be associated with exemplary performance, while senior executives tend to prefer bonds, shares, and other incentives that encourage them to remain with the company.

2 – Feelings

In the second phase, the HR employee considers how the feelings toward a particular reward influence how it is viewed.

For junior employees, the employee contends that a dearness allowance is a strong motivator. The allowance, which is built into an employee’s salary to offset inflationary cost-of-living pressures, is one way for these employees to feel valued and appreciated.

For senior executives, the reward of part ownership of the company makes them feel proud of their contributions to building a business over the long term.

3 – Evaluation

This was the first time the HR manager took an active, in-depth look at employee incentivization. In the past, the firm had instructed HR to reward employees with extra financial compensation irrespective of their seniority level.

In the evaluation phase, the manager deduces that employee compensation is not something the company can take lightly moving forward.

She also determines that her initiative to research attractive compensation for different cohorts will have a positive impact on the company’s productivity and culture.

Within reason, however, the HR department must listen to the contributions and suggestions of employees and then act on them – particularly if the current remuneration system is not meeting an employee’s needs.

4 – Analysis

In the literature, countless models and theories have been devised to explain sources of motivation in the workforce.

Some posit that motivation can be increased via certain leadership styles, while others focus on company policies, supervisor support, interpersonal relationships, and the idea of reciprocity.

According to the Society for Human Resource Management, however, around 85% of workers said compensation was important or very important to their job satisfaction.

What’s more, 92% said the presence of benefits could be the difference between choosing one employer over another.

For senior executives who are paid well, the most effective benefits are those that have monetary value but do not necessarily involve a direct payment of cash. These include stock options, titles, and health care coverage.

Junior employees are also likely to value health care coverage and access to schemes such as paid parental leave. But since they are paid less than their senior counterparts, bonuses and raises are still valued the most.

These extra funds are used to pay for basic needs such as food, shelter, and safety in an inflationary environment, while non-monetary benefits for executives fulfill needs related to self-esteem and self-actualization.

The needs of both junior and senior employees are described in detail by Maslow in his hierarchical pyramid.

5 – Conclusion and action plan

Moving forward, the HR manager strongly recommends that this targeted approach to employee reward and recognition be written into company procedures.

Under the proviso that employee performance is maintained, it is imperative to routinely appraise compensation schemes and develop a tailored approach for each of the employee cohorts.

This strategy may be more expensive than alternatives, but the HR manager concludes by remarking that a twelve-month trial period may be prudent to see whether the cost is offset by more motivated and productive employees.

Gibbs’ reflective cycle – Tesco

In 2013, British supermarket chain Tesco was faced with a major scandal after horse meat was detected in its beef burger products.

The scandal caused a significant drop in sales and negatively impacted consumer confidence in the Tesco brand. Let’s explain how the incident played out and how the company responded with a hypothetical Gibbs’ reflective cycle.

Description

Tens of millions of burger and related beef products with withdrawn from shelves across Europe in the wake of the scandal. Some of the products – including Tesco’s own brand burgers – contained up to 29% horse meat.

The outcome of the tainted beef was a decrease in consumer confidence in meat products. One report found that 60% of consumers had altered their shopping habits, with 30% buying less red meat overall and 24% choosing vegetarian options.

Feelings

Tesco was shocked, disappointed, and concerned for the company’s reputation initially. The company ran prominent ads in several newspapers where it acknowledged the seriousness of the situation and offered a full refund.

In one ad, the company’s remorse was evident: “We will work harder than ever with all our suppliers to make sure this never happens again.”

Evaluation

For Tesco, the negative aspects of the event were a detrimental impact on brand image and consumer confidence. Consumers were economic victims because they paid for a product they did not receive. But horse meat also poses a health risk because it is often tainted with horse-specific pharmaceuticals that are banned from human consumption.

While there were few positives to take from the scandal, it did force the company to evaluate its supply chain practices. Then-CEO Philip Clarke later noted at the Institute for Global Food Security that “This has been a wake-up call for us all, and I see it being a pivotal moment for our industry.”

Analysis

It was later concluded that Tesco’s somewhat opaque supply chain was a primary contributor to the problem. Horse meat was of course labeled as beef, but identifying the point at which the beef became tainted proved difficult.

The factory that supplied Tesco with its private-label brand of beef burgers, for example, used ingredients from up to 40 different suppliers and the exact mix could vary every 30 minutes. Eventually, it was discovered that meat testing positive for horse DNA originated from a factory near the border with Ireland.

The company that operated the factory processed meat for pet food and also sourced product from a Dutch businessman who was known to cut beef with horse meat. It also emerged that workers from Tesco’s Polish suppliers mixed horsemeat with defrosted beef that was sometimes so old it had turned green.

Conclusion

The situation taught Costco that transparency is key in its supply chains and relationships with suppliers. While the company claimed it had been a victim of fraud, it nevertheless admitted that its supply chain needed to be modernized and made more transparent to reflect the increased global demand for meat products.

Action plan

Tesco undertook several corrective measures. It hired a senior executive from the National Farmers’ Union (NFU) to restore consumer confidence in its products and improve the company’s relationship with farmers and suppliers. What’s more, the company committed to sourcing more of its meat from British suppliers wherever possible.

Clarke also announced at an NFU conference that he wanted to introduce a more transparent supply chain. This would entail a more comprehensive system of DNA testing that he believed would set a new standard for all supermarkets.

Separate from Tesco’s action plan was a report published by the governmental Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. The report made several recommendations, chief among which was that consumer food safety and protection from food-related crime be made a top priority. The governmental body also called for more data-sharing and the development of effective crises and contingency plans.

| Related Frameworks | Definition | Focus | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle | A structured model for reflective practice, consisting of six stages: Description, Feelings, Evaluation, Analysis, Conclusion, and Action Plan. | Facilitates systematic reflection on experiences to promote learning and personal development. | Reflective Practice, Experiential Learning |

| Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle | Presents a cyclical model of learning, comprising four stages: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation. | Focuses on the process of learning from experience through reflection and action. | Education, Training, Personal Development |

| Schön’s Reflective Practice Model | Introduces two types of reflection: Reflection-in-Action (during the experience) and Reflection-on-Action (after the experience), emphasizing the importance of professional knowledge and the role of intuition and improvisation in practice. | Highlights the role of reflection in professional practice and the development of tacit knowledge. | Professional Development, Education |

| Borton’s Reflective Framework | Consists of three key questions: “What? So what? Now what?” encouraging individuals to explore the situation (What happened?), reflect on its significance (So what?), and determine future actions (Now what?). | Provides a simple yet effective structure for reflective practice and decision-making. | Personal Development, Problem-Solving |

| Rolfe et al.’s Reflective Framework | Comprises three key questions: What? So what? Now what? Similar to Borton’s framework but emphasizes the importance of exploring emotions, beliefs, and values in the reflective process. | Integrates emotional and cognitive aspects of reflection to enhance learning and personal growth. | Nursing, Healthcare, Personal Development |

| Brookfield’s Critical Reflection | Encourages individuals to critically analyze assumptions, beliefs, and power dynamics underlying their experiences, challenging existing perspectives and fostering deeper understanding and change. | Emphasizes critical thinking and reflexivity in the reflective process to promote transformative learning. | Education, Adult Learning, Social Change |

| Atkins and Murphy’s Reflective Model | Comprises four stages: Description, Analysis, Outcomes, and Action. Similar to Gibbs’ model but incorporates an additional stage for identifying outcomes and planning future actions based on the reflection. | Provides a structured approach for reflective practice with a focus on learning outcomes and action planning. | Professional Development, Education |

| Mezirow’s Transformative Learning | Focuses on the process of perspective transformation through critical reflection on assumptions and beliefs, leading to profound changes in understanding, identity, and behavior. | Emphasizes the role of critical reflection in challenging and reconstructing meaning frameworks to facilitate transformative learning. | Education, Adult Learning, Personal Development |

Gibbs’ reflective cycle vs. Kolb’s Reflective Cycle

Kolb and Gibb’s models are both intended to enable learning through direct experience.

Therefore, enabling individuals to learn based on action.

Whereas Gibbs’ model has five stages of assessing any real-world situation.

Kolb’s model has four stages instead:

- Concrete experience.

- Reflective observation.

- Abstract conceptualization.

- And active experimentation.

Kolb’s model is way more skewed toward experience-based learning, where active experimentation becomes a critical component of the iterative learning process.

Whereas Gibbs’ model is still based on experience-based learning, yet it provides more of an analytical and structured framework to assess these experiences.

Key takeaways and examples

- Gibbs’ reflective cycle is a framework giving structure to the process of learning from experience. The framework was developed by Dr. Graham Gibbs in 1988.

- The cyclical nature of Gibbs’ reflective cycle is best suited to fostering continuous improvement of repeated experiences. However, it can also be used to reflect on standalone experiences.

- Gibbs’ reflective cycle is based on six stages: description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusion, and action plan. Each stage encourages self-reflection through the posing of multiple questions.

Key Highlights

- Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle: Developed by Dr. Graham Gibbs in 1988, it is a framework for structured reflection on learning from experience. The cycle consists of six stages: description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusions, and action plan.

- Purpose of Reflection: Reflecting on experiences is crucial for effective learning. Without reflection, experiences may be forgotten, and their learning potential lost. Reflection helps generate generalizations and concepts that can be applied to new situations.

- Experiential Learning: Gibbs’ reflective cycle supports experiential learning, where learning occurs through experiences. The cycle can be applied to both structured and unstructured learning scenarios.

- Tailored Approach: The cycle’s cyclical nature makes it suitable for continuous improvement in recurring experiences, as well as for one-time situations. It encourages individuals to learn from both successes and failures.

- Advantages:

- Provides a structured framework for analyzing experiences.

- Can be used for continuous improvement and planning based on past experiences.

- Tailored approach for different situations and levels of expertise.

- Disadvantages:

- Six Stages of Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle:

- Description: Describe the situation or experience objectively.

- Feelings: Reflect on the emotions and thoughts associated with the experience.

- Evaluation: Assess the positive and negative aspects of the experience.

- Analysis: Analyze the situation using relevant theory and context.

- Conclusions: Draw conclusions based on key findings and insights.

- Action Plan: Develop an action plan for responding differently in similar situations in the future.

- Examples of Applying Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle:

- Getting a Promotion: Applying the cycle to a scenario of being promoted and facing challenges in asserting authority and making decisions.

- Startup Accelerator: Reflecting on the process of developing incentive programs for junior employees and senior executives within a startup accelerator.

- Tesco Scandal: Reflecting on how British supermarket Tesco responded to a scandal involving horse meat found in beef products, and the lessons learned.

- Comparison with Kolb’s Reflective Cycle: While both models emphasize experiential learning, Kolb’s model focuses on four stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. Gibbs’ model provides a more structured and analytical approach to reflecting on experiences.

- Key Takeaways: Gibbs’ reflective cycle is a valuable tool for individuals, organizations, and industries to learn from experiences, improve decision-making, and enhance personal and professional development.

Types of Organizational Structures

Siloed Organizational Structures

Functional

Divisional

Open Organizational Structures

Matrix

Flat

How do you write a Gibbs reflective cycle?

The six stages of Gibbs’ reflective cycle comprise:

Who is Gibbs reflective cycle used for?

The framework gives structure to the process of learning from experience through six stages: description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusions, and action plan. It’s beneficial as a review process for individuals within the organizations as it helps them better understand their capabilities as they move to a structured way to assess any situation by objectively analyzing it.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of Gibbs reflective cycle?

A core advantage is that Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle introduces a structured way to assess the individuals within an organization. A disadvantage is that for it to work, it needs to be done objectively, without prejudice. Otherwise, it becomes useless and detrimental to the team using it.

Connected Learning Frameworks

Related Strategy Concepts: Read Next: Mental Models, Biases, Bounded Rationality, Mandela Effect, Dunning-Kruger Effect, Lindy Effect, Crowding Out Effect, Bandwagon Effect, Decision-Making Matrix.

Main Free Guides: