The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is a financial metric used to assess the potential profitability of an investment or project. It represents the discount rate at which the net present value (NPV) of the cash flows generated by the investment becomes zero. In other words, it’s the rate of return that an investment is expected to generate. The IRR is calculated using the following formula:

0 = CF0 + (CF1 / (1 + IRR)^1) + (CF2 / (1 + IRR)^2) + … + (CFn / (1 + IRR)^n)

Where:

- “CF0” represents the initial cash outflow (or investment cost) at time zero.

- “CF1,” “CF2,” …, “CFn” represent the expected cash inflows or outflows for each period from 1 to n.

- “IRR” is the internal rate of return, which you’re trying to calculate.

The IRR is the rate that, when used as the discount rate in this equation, makes the sum of the present values of all cash flows (both inflows and outflows) equal to zero. In practical terms, you would typically use numerical methods or financial software to solve for IRR because it’s not always easy to solve for it algebraically.

| Aspect | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Concept Overview | The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is a fundamental financial metric used to evaluate the profitability and attractiveness of an investment or project. It represents the discount rate at which the net present value (NPV) of all cash flows associated with an investment becomes zero. In simpler terms, the IRR is the expected annualized return on an investment, considering both the initial investment and subsequent cash flows over its lifespan. It is a widely used tool in financial decision-making. |

| Key Characteristics | The IRR is characterized by several key features: 1. Discounted Cash Flows: It accounts for the time value of money, giving greater weight to cash flows received sooner. 2. Expected Return: It provides insight into the expected annual rate of return on an investment. 3. Decision Criterion: Typically, if the IRR exceeds the cost of capital (hurdle rate), the investment is considered acceptable; otherwise, it may be rejected. |

| Calculation | Calculating the IRR involves finding the discount rate that equates the present value of future cash flows to the initial investment. This is often done using iterative methods or financial calculators/software. The IRR is the rate at which the equation NPV = 0 is satisfied. |

| Investment Decision | In investment decision-making, if the calculated IRR exceeds the organization’s hurdle rate or required rate of return, the investment is typically deemed financially viable and acceptable. If the IRR falls below the hurdle rate, the investment may be rejected as it is not expected to generate returns above the cost of capital. |

| Multiple IRRs | – In some cases, projects with complex cash flow patterns can result in multiple IRRs, which can complicate decision-making. Analysts should exercise caution in interpreting IRR when this occurs, as it may not provide a clear indication of investment viability. |

| Comparison to Hurdle Rate | – A common practice is to compare the IRR directly to the organization’s cost of capital or hurdle rate. If the IRR exceeds this rate, the investment is generally considered favorable because it is expected to generate returns greater than the cost of obtaining capital. The greater the margin by which IRR exceeds the hurdle rate, the more attractive the investment. |

| Advantages | – IRR offers several advantages, including: 1. Simplicity: It provides a single percentage that summarizes the investment’s expected return. 2. Focus on Returns: It emphasizes the return aspect, which is often a primary concern for investors. 3. Time-Value Consideration: It accounts for the time value of money, making it a more precise metric. |

| Limitations | – IRR has limitations, such as: 1. Multiple IRRs: Complex cash flows can lead to multiple IRRs, making interpretation challenging. 2. Ignoring Scale: It doesn’t consider the absolute scale of cash flows or initial investments. 3. Reinvestment Assumption: It assumes reinvestment of cash flows at the IRR rate, which may not always be realistic. 4. Mutually Exclusive Projects: It may not be suitable for comparing mutually exclusive projects with different cash flow patterns. |

| Use in Decision-Making | – Organizations use the IRR as a crucial tool in making investment decisions. It helps determine whether projects or investments meet financial performance expectations. However, IRR should be used in conjunction with other financial metrics and qualitative factors to make well-informed decisions. |

| Risk and Uncertainty | – IRR analysis should consider risk and uncertainty. Sensitivity analysis and scenario planning can help assess how variations in cash flow assumptions affect the IRR. In situations of high risk or uncertainty, organizations may use higher hurdle rates to account for potential variability. |

| Strategic Implications | – IRR considerations can align with an organization’s strategic objectives. Investments with higher IRRs may be prioritized if they contribute more significantly to achieving strategic goals. Conversely, investments with lower IRRs may be accepted if they provide essential strategic benefits beyond financial returns. |

| Communication and Reporting | – Communicating IRR findings effectively is essential for decision-makers and stakeholders. Clear presentations, sensitivity analyses, and concise explanations are crucial for conveying the implications of IRR analysis. Stakeholder buy-in and understanding are essential for successful decision-making. |

| Continuous Review | – IRR is not a one-time calculation. It should be revisited as projects evolve, assumptions change, and new information becomes available. Continuous review ensures that investment decisions remain aligned with evolving organizational priorities and market conditions. |

| Global Considerations | – In a global context, IRR calculations may require adjustments to account for factors like currency exchange rates, political stability, and international tax considerations. Evaluating cross-border investments may necessitate a deeper understanding of global financial dynamics. |

Understanding Internal Rate of Return (IRR):

What is Internal Rate of Return (IRR)?

The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is a critical financial metric used to assess the profitability and attractiveness of an investment project. It represents the discount rate at which the net present value (NPV) of an investment becomes zero, indicating the rate of return that the investment is expected to generate.

Key Elements of Internal Rate of Return (IRR):

- Cash Flows: The expected cash inflows and outflows associated with the investment project over its lifetime.

- Discount Rate: The rate at which future cash flows are discounted to their present value.

- IRR: The rate at which the NPV of the investment equals zero, signifying the project’s internal rate of return.

Why Internal Rate of Return (IRR) Matters:

Understanding the significance of IRR is essential for investors, financial analysts, and businesses as it provides valuable insights into the potential return and risk associated with investment projects.

The Impact of Internal Rate of Return (IRR):

- Profitability Assessment: IRR helps assess whether an investment project is expected to generate returns that exceed its cost of capital.

- Comparative Analysis: It enables decision-makers to compare multiple investment opportunities by evaluating their IRRs and selecting those with the highest potential returns.

- Capital Allocation: Businesses use IRR as a criterion for allocating capital among various projects to maximize overall returns.

Benefits of Using Internal Rate of Return (IRR):

- Sophisticated Analysis: IRR accounts for the time value of money, making it a more sophisticated metric than the payback period.

- Risk Assessment: It provides insights into the risk associated with an investment by indicating the minimum rate of return required for the project to be financially viable.

Challenges of Using Internal Rate of Return (IRR):

- Complexity: Calculating IRR can be complex, especially for projects with irregular cash flows or multiple changes in cash flow direction.

- Multiple IRRs: Some investment projects may have multiple IRRs, leading to confusion in interpretation.

Challenges in Using Internal Rate of Return (IRR):

Understanding the challenges and limitations associated with IRR is crucial for making informed investment decisions and addressing potential issues.

Complexity:

- Irregular Cash Flows: Calculating IRR for projects with irregular cash flows, such as those with multiple changes in cash flow direction, can be challenging.

- Numerical Methods: Numerical methods or software tools are often required to find the IRR, adding complexity to the analysis.

Multiple IRRs:

- Non-Conventional Cash Flows: Investment projects with non-conventional cash flows, including multiple changes in cash flow direction, can result in multiple IRRs, making interpretation difficult.

- Solution: Analysts should be cautious and consider the context when dealing with projects that exhibit multiple IRRs.

Internal Rate of Return (IRR) in Action:

To better understand IRR, let’s explore how it functions in various investment scenarios and what it reveals about the financial viability of projects.

Real Estate Investment:

- Scenario: A real estate developer plans to invest in a commercial property development project.

- IRR in Action:

- Cash Flow Projections: The developer estimates rental income, operating expenses, and the initial investment to calculate the project’s IRR.

- Decision-Making: A higher IRR may indicate a more attractive investment opportunity, potentially leading to project selection.

Infrastructure Development:

- Scenario: A government agency is considering investing in a new transportation infrastructure project.

- IRR in Action:

- Initial Cost: The agency calculates the IRR by comparing the infrastructure’s cost to the expected economic benefits over time.

- Public Policy: A positive IRR suggests that the project could provide a return on investment to the community and enhance economic development.

Corporate Expansion:

- Scenario: A multinational corporation is evaluating the IRR of expanding its manufacturing facilities in a new market.

- IRR in Action:

- Risk Assessment: The corporation calculates the IRR to assess the potential return on investment and the associated risks.

- Global Strategy: A favorable IRR may support the decision to expand into a new market, depending on other strategic considerations.

Examples and Applications:

- IRR for Bond Investments:

- Investors assess the IRR of bonds to determine whether the yield-to-maturity (YTM) exceeds their required rate of return.

- Example: If a bond with a face value of $1,000 offers annual coupon payments of $60 and matures in 5 years, its IRR is approximately 6%.

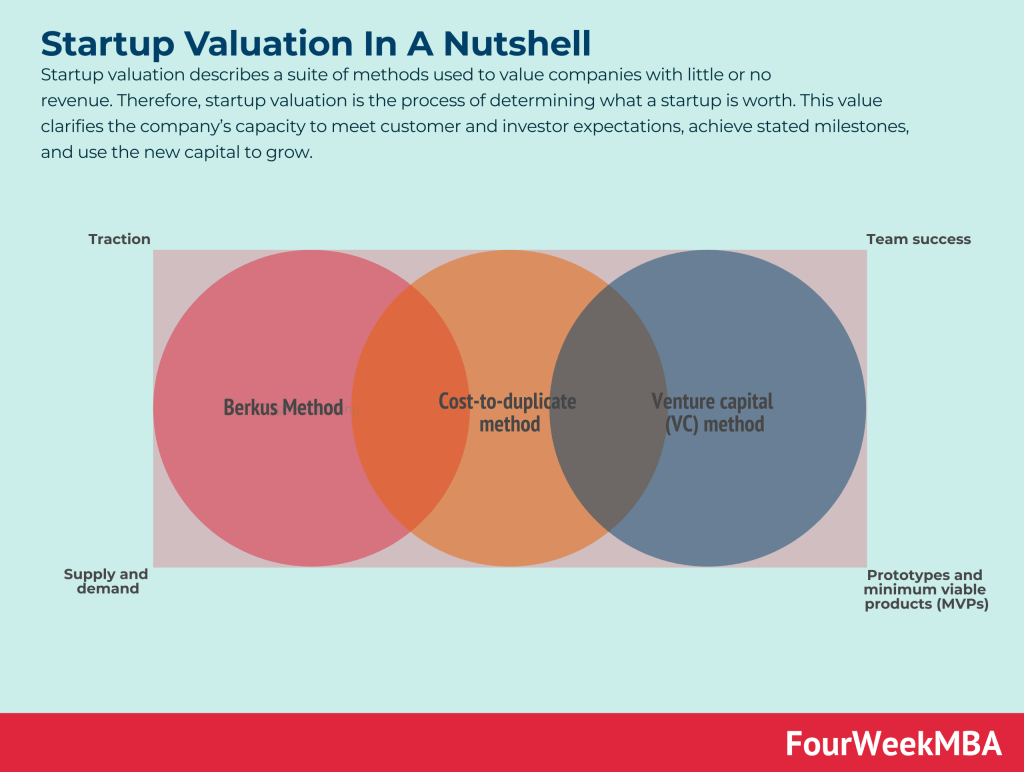

- IRR for Start-up Valuation:

- Venture capitalists use IRR to evaluate the potential return on investment in early-stage start-ups.

- Example: If a venture capitalist invests $500,000 in a start-up and expects a future exit with a net profit of $2 million, the IRR can be calculated based on the investment horizon.

- IRR for Capital Budgeting:

- Corporations use IRR as a key metric in capital budgeting to assess the feasibility of long-term projects.

- Example: A company evaluates the IRR of a new production facility to determine whether the expected returns meet its minimum required rate of return.

Applications and Use Cases:

- Project Ranking:

- IRR helps rank and prioritize investment projects by identifying those with the highest expected returns.

- Risk Assessment:

- Investors and lenders use IRR to assess the risk associated with various investment opportunities by comparing them to the required rate of return.

- Budgeting and Resource Allocation:

- Companies use IRR as a criterion for allocating financial resources among competing projects, aiming to maximize overall returns.

- Comparing Investment Options:

- Decision-makers compare IRRs when evaluating multiple investment opportunities to determine which projects align with their financial objectives.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is a crucial metric in investment analysis, providing a sophisticated and comprehensive way to assess the profitability and risk associated with investment projects.

The applications of IRR are diverse and extend across various industries and financial contexts, making it an indispensable tool for decision-makers. While it presents challenges related to complexity and the potential for multiple IRRs, its ability to account for the time value of money and provide insights into potential returns makes it a valuable metric for evaluating investment opportunities. By acknowledging the significance of IRR and complementing it with other financial metrics, stakeholders can navigate the complexities of investment analysis and make informed decisions to achieve their financial objectives.

Key Highlights

- Understanding Internal Rate of Return (IRR):

- Key Elements of Internal Rate of Return (IRR):

- Why Internal Rate of Return (IRR) Matters:

- Profitability Assessment: Helps assess whether an investment project generates returns exceeding its cost of capital.

- Comparative Analysis: Enables comparison of multiple investment opportunities.

- The Impact of Internal Rate of Return (IRR):

- Profitability Assessment: Determines if an investment generates returns above the cost of capital.

- Comparative Analysis: Facilitates comparison of projects to prioritize investment opportunities.

- Benefits of Using Internal Rate of Return (IRR):

- Sophisticated Analysis: Accounts for the time value of money.

- Risk Assessment: Provides insights into investment risk.

- Challenges of Using Internal Rate of Return (IRR):

- Complexity: Calculation can be complex for projects with irregular cash flows.

- Multiple IRRs: Some projects may have multiple IRRs, making interpretation difficult.

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR) in Action:

- Real Estate Investment: Evaluates potential returns from commercial property development.

- Infrastructure Development: Assesses economic benefits of transportation projects.

- Corporate Expansion: Determines returns from expanding manufacturing facilities.

- Examples and Applications:

- IRR for Bond Investments: Assesses bond yields compared to required rates of return.

- IRR for Start-up Valuation: Evaluates potential returns from investing in early-stage start-ups.

- IRR for Capital Budgeting: Determines feasibility of long-term projects.

- Applications and Use Cases:

- Project Ranking: Helps prioritize investment projects based on expected returns.

- Risk Assessment: Assists in evaluating risk by comparing IRRs to required rates of return.

- Budgeting and Resource Allocation: Guides allocation of financial resources among competing projects.

- Conclusion:

- Significance of IRR: Crucial for evaluating profitability and risk of investment projects.

- Diverse Applications: Widely used across industries and financial contexts.

- Challenges and Benefits: Provides sophisticated analysis but can be complex, especially with irregular cash flows.

- Importance of Complementary Metrics: Should be used alongside other financial metrics for informed decision-making.

| Capital Budgeting Method | Description | Formula | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Net Present Value (NPV) | Calculates the present value of future cash flows minus the initial investment. If NPV is positive, the project is considered acceptable. | NPV = Σ(CFt / (1 + r)^t) – Initial Investment | Initial Investment: $100,000 Cash Flows (Year 1-5): $30,000, $35,000, $40,000, $45,000, $50,000 Discount Rate (r): 10% NPV = $24,289.40 |

| Internal Rate of Return (IRR) | Determines the discount rate that makes the NPV of future cash flows equal to zero. Projects with IRR higher than the required rate of return are accepted. | NPV = Σ(CFt / (1 + IRR)^t) – Initial Investment | Initial Investment: $200,000 Cash Flows (Year 1-5): $50,000, $45,000, $40,000, $35,000, $30,000 IRR ≈ 15.71% |

| Payback Period | Measures the time it takes to recover the initial investment from the project’s cash flows. Shorter payback periods are generally preferred. | Payback Period = Initial Investment / Annual Cash Flow | Initial Investment: $150,000 Annual Cash Flow: $40,000 Payback Period = 3.75 years |

| Profitability Index (PI) | Compares the present value of cash inflows to the initial investment. Projects with a PI greater than 1 are typically considered favorable. | PI = Σ(CFt / (1 + r)^t) / Initial Investment | Initial Investment: $80,000 Cash Flows (Year 1-5): $25,000, $28,000, $30,000, $32,000, $35,000 Discount Rate (r): 8% PI = 1.38 |

| Accounting Rate of Return (ARR) | Calculates the average annual accounting profit as a percentage of the initial investment. Projects with higher ARR may be favored. | ARR = (Average Annual Accounting Profit / Initial Investment) * 100% | Initial Investment: $120,000 Average Annual Accounting Profit: $18,000 ARR = 15% |

| Modified Internal Rate of Return (MIRR) | Similar to IRR but assumes reinvestment at a specified rate, addressing potential issues with IRR’s multiple rates problem. | MIRR = (FV of Positive Cash Flows / PV of Negative Cash Flows)^(1/n) – 1 | Negative Cash Flows: $200,000 Positive Cash Flows: $50,000, $55,000, $60,000 Reinvestment Rate: 10% MIRR ≈ 12.63% |

| Discounted Payback Period | Similar to the payback period but accounts for the time value of money by discounting cash flows. | Discounted Payback Period = Number of Years to Recover Initial Investment | Initial Investment: $90,000 Discount Rate: 12% Cash Flows (Year 1-5): $30,000, $32,000, $34,000, $36,000, $38,000 Discounted Payback Period = 3.18 years |

Connected Financial Concepts

Main Free Guides: